Optimal panic levels

Or, why everyone is mad at Bill Gates

“This is no time to panic.”

Remember that iconic scene from Toy Story where Woody and Buzz Lightyear discuss the merits of panicking? They raise today’s fundamental question: When is the perfect time to panic?

Verging on pro-panic

It’s widely accepted that panic is a bad, unproductive feeling. I’m going to zag here—I’m a younger sibling and can’t help it—and argue that there is utility in panic. While I’m not exactly in favor of panic, I think it can be a useful lens through which to consider:

Who should panic and when.

Why so many people are mad at Bill Gates for his recent Gates Notes.

Before we get to my answer, I want to provide some context.

Bill Gates published Three tough truths about climate on his blog, GatesNotes. His argument was essentially: don’t panic about climate change, it’s not the only crisis, and human suffering still matters (food, poverty, etc.)

In response, just about everyone had something to say. (Roughly, the left and climate community were like: wtf, this isn’t what we need right now; the right was exultant but clearly didn’t do the reading; entrepreneurs and scientists pointed out that he was making an entirely reasonable argument.)

I’m not going to discuss the merits of Gates’s argument, as people smarter than me have done so at great length. This piece is about how people respond to being told not to panic, and particularly why Gates’s post touched something raw.

What is panic for?

I think traditionally, people say the ideal amount of panic is none. I don’t think this is correct. I see panic as an emotional response to a threat. Panic communicates, “something is wrong, I feel out of control, and I can’t fix it myself.” Now, most of the time we’d like to dial the emotional register down to “concern” or “urgency.” But in practice, life often runs on cruder settings—either nobody cares, or people are panicking.

If you run a household (or representative government), panic is something like a flashing warning light on the dash. The warning light doesn’t understand why the oil is low, nor can it resolve the issue, but…it has utility! This isn’t to say that every panic is rational—not all panic is communicating a real threat. But wholesale suppression of panic is definitively bad, and enables groups to sleepwalk into disaster.

Panic also generates demand for leadership. Leaders don’t panic. Leaders respond to panic. Panic specifically indicates “I want someone else to resolve this!” If you’re not in a position of power—as a child in a family, or a poor person in a large country, you might not be able to resolve the the threat but you can panic! You still have power! The expression “cooler heads prevail” suggests exactly this transfer of both responsibility and transformation of emotion.

I’m not known for my subtlety. The mapping in the previous paragraphs is probably clear: people were panicking about climate change because they wanted someone to do something about it. Gates thought they should stop.

Which returns us to the core of our inquiry: Who gets to panic? Should they panic? And what happens when they do?

A unified theory of panic

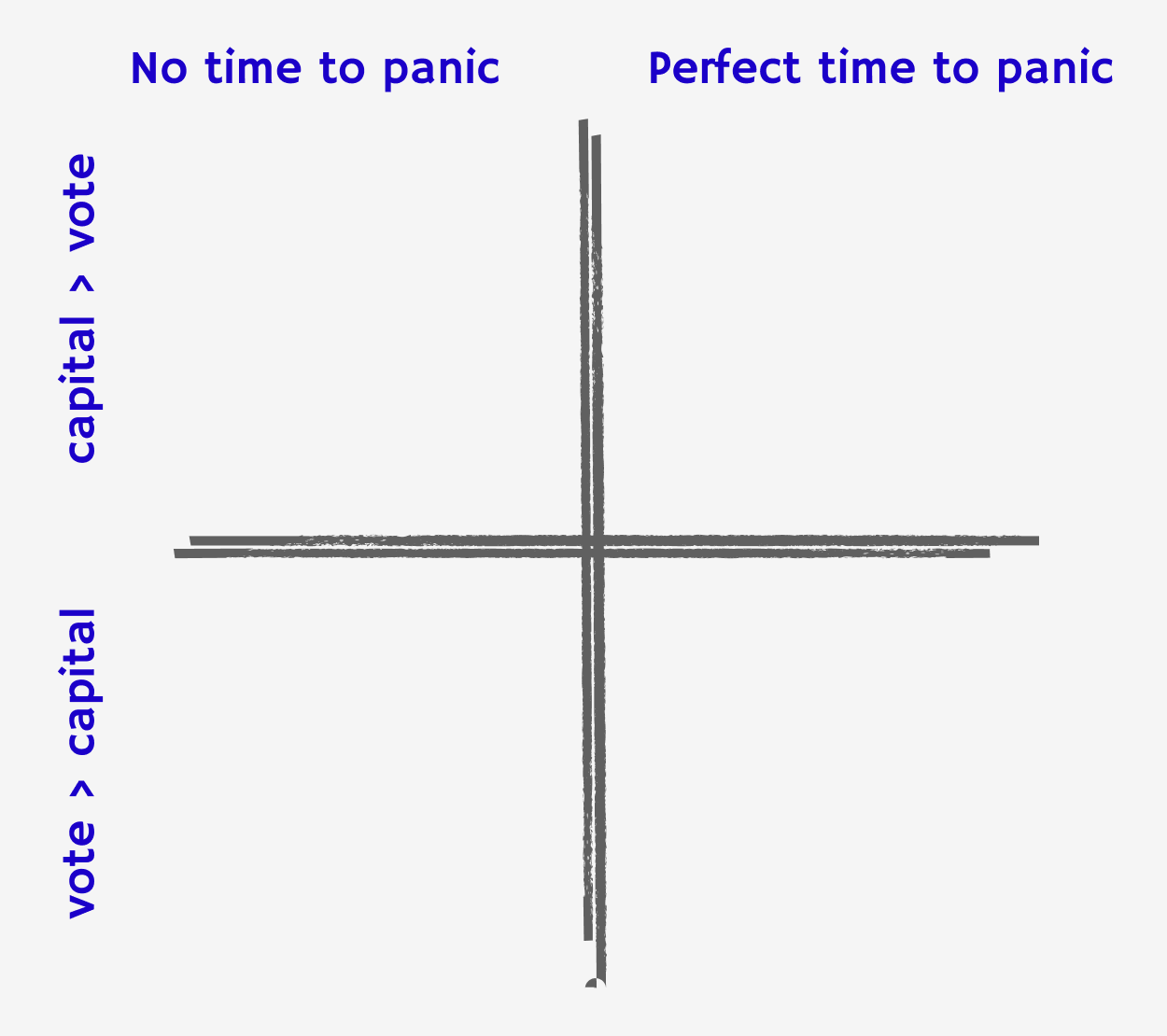

Like all thoughtful and nuanced arguments, ours starts with a dichotomy. Let’s separate society into two groups: one group is defined by influencing society more by allocating their capital than by voting. The second is the reverse; they have more comparative voting power than influence via capital.

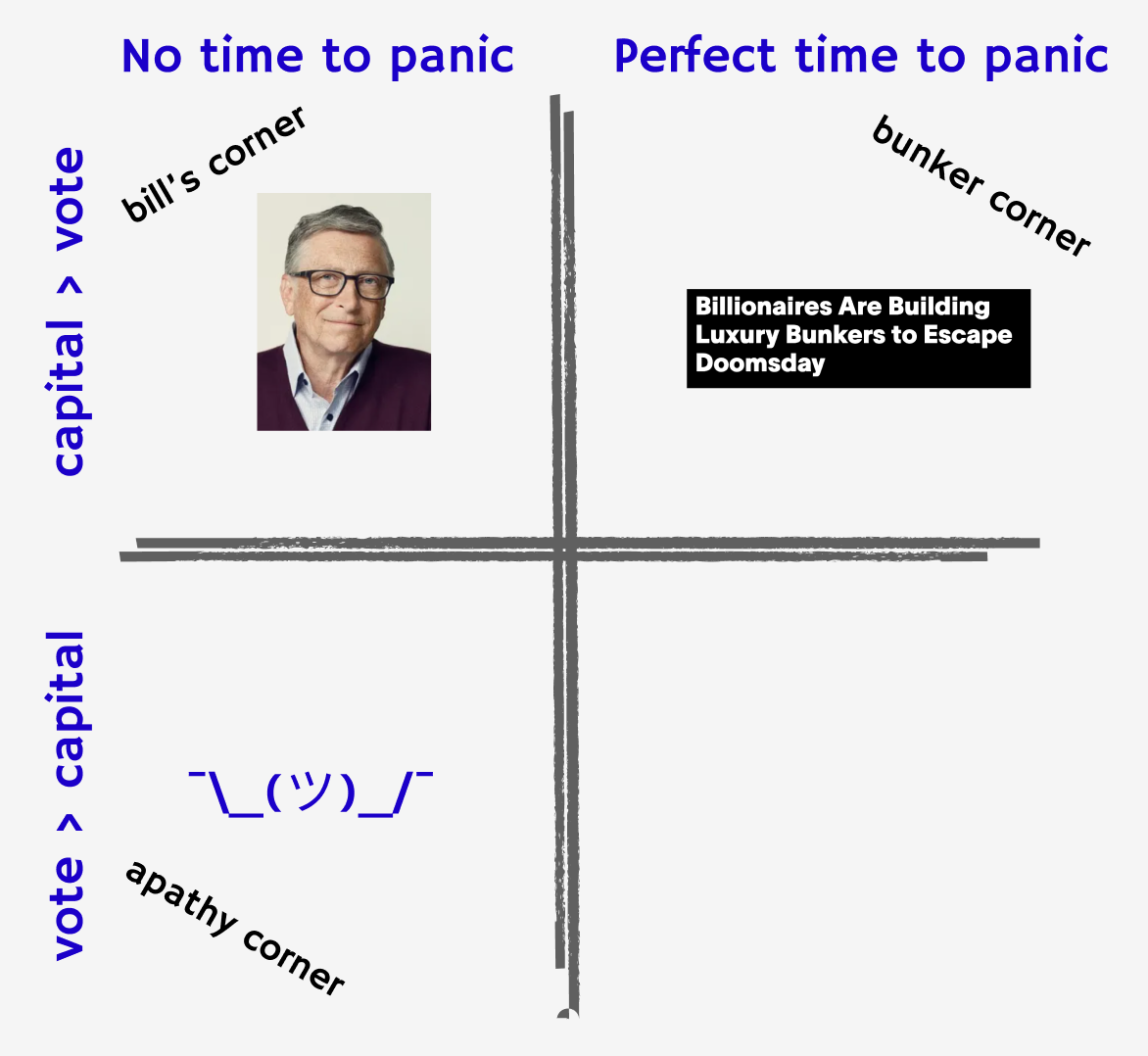

And, doubling down on dichotomies, let’s say there is, on any topic, two states: “This is no time to panic” and “This is the perfect time to panic.” Now we have a rubric to describe where fear lives in society. Empty, it looks like this this:

Let’s describe the behavior of each quadrant, and grade them on *community* utility.

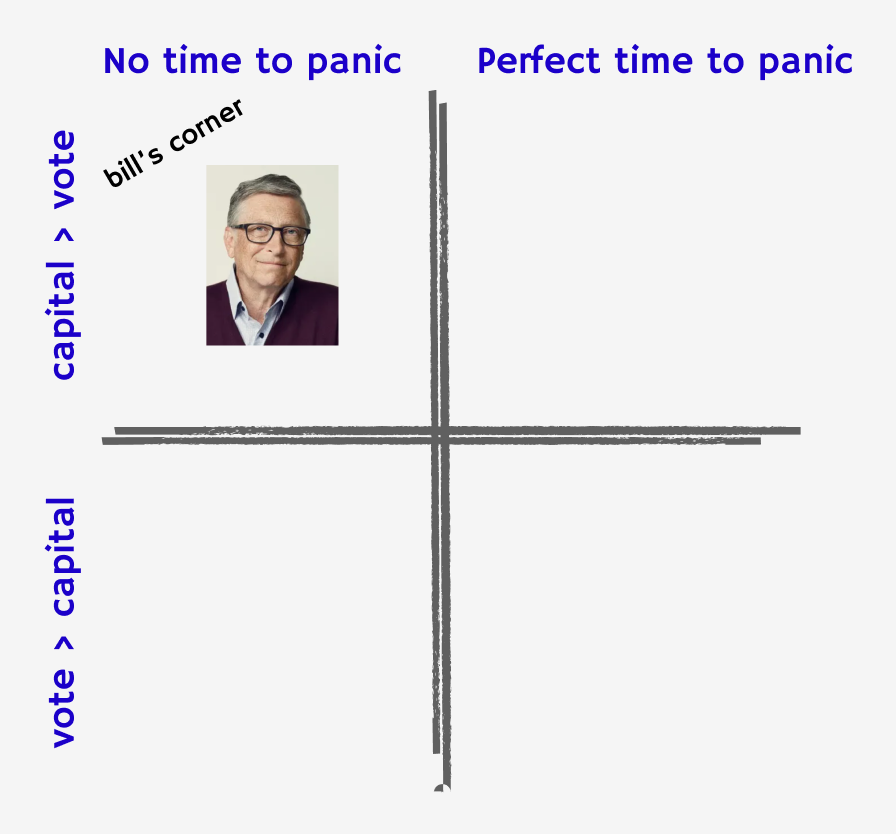

Top left (no panic + capital):

This is a happy corner. Investors are cool-headed, allocating capital objectively with long timelines. They can justify not stockpiling gold and building bunkers because now is no time to panic—things are under control, and there are opportunities to invest. This is where Bill Gates is. This is Bill’s Corner.1

10/10, best case scenario

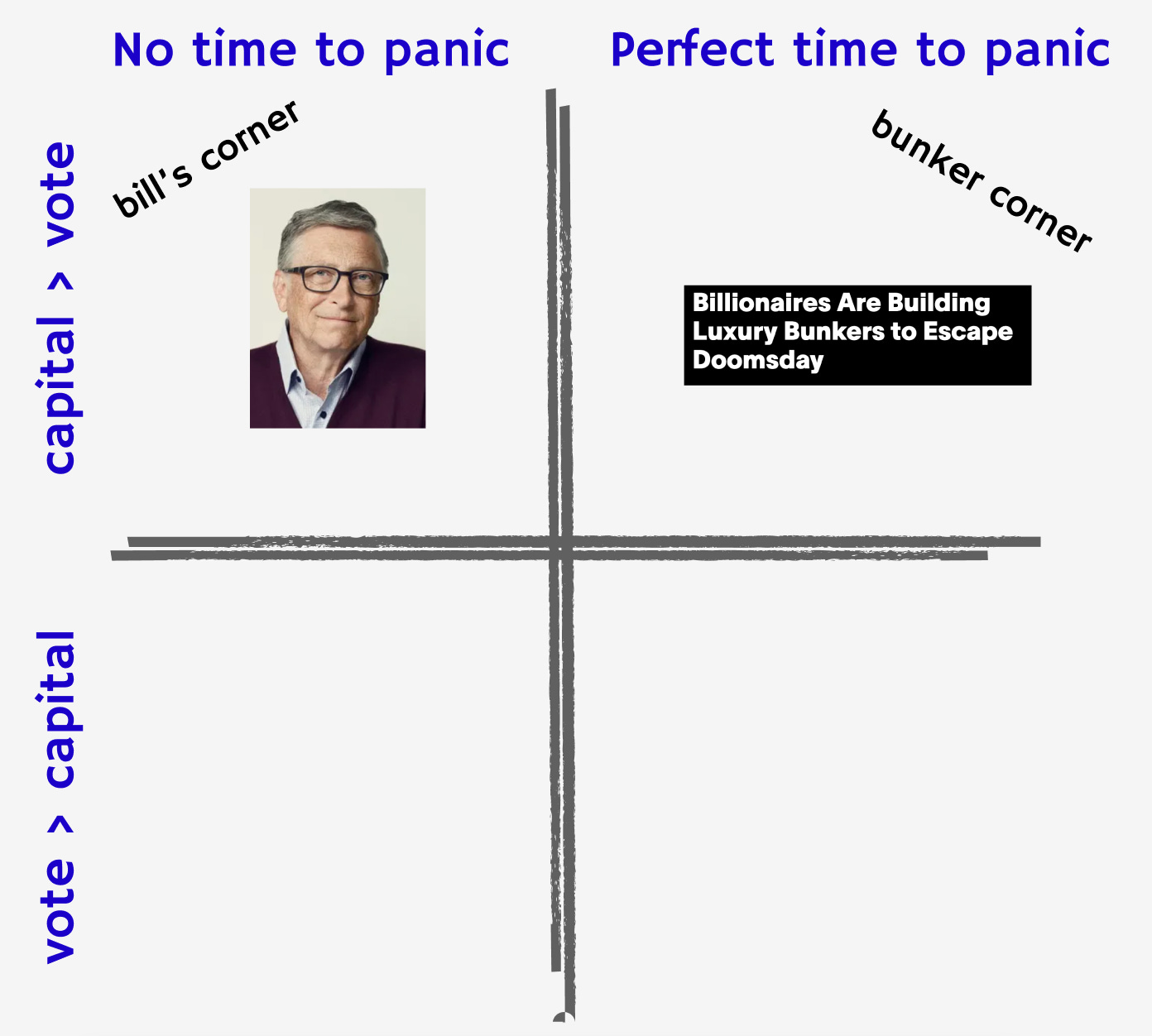

Top right (panic + capital):

I’m going to call this the bunker corner. When capital allocators panic, everything is bad. Capital flees to hard assets, markets crash, rich folks desperately try to protect their wealth, our veneer of civilization wears thin, and a broad descent into Hobbesian darkness looms. Of all the quadrants, this is the absolute worst for people, society, and especially things like “progress.” It must be avoided at all costs, hence the cultural emphasis on leaders not panicking.

0/10, worst case scenario

Bottom left (no panic + vote):

When people without significant capital to allocate encounter a problem and think, “meh, what can I do, I’m just going to ignore it” they exert very little influence on society. By not panicking, they don’t generate demand for leadership. They don’t force government to take collective action on their behalf. When facing a problem that threatens people the general public, an insufficiently intense response enables inaction by the government.

Used to be here:

dramatic increases in home and health insurance costs, rising costs of housing

Currently here:

Slow-burn environmental harms (PFAS, microplastics)

Background deaths we treat as normal (traffic fatalities)

Blatant corruption and insider trading by politicians

Broad adoption of addictive systems (online gambling, short-form video melting people’s brains)

This is apathy corner, and it is mostly bad. There are situations where panic isn’t warranted, so it’s not always bad.

3/10, not ideal

Bottom right (panic + vote):

This is the activist corner. The people are panicking about _______ (housing, immigration, affordability, inflation, the climate). They demand that someone do something! Their panic is a lever for collective action. Existing in a state of panic is not ideal on an individual level (lots has been written here) but it has collective benefits: an important problem can get attention, and theoretically get resolved by someone else.

7/10, better than doing nothing, costly at an individual level

So, layering on the implication to society (from my extremely rigorous scoring system), we end up with the below. The obvious takeaway is that, when facing a problem, the most pro-social outcomes are possible when rich people think everything is going to be fine, and everyone else is panicking enough to make sure the government addresses the problem. If everyone panics, the government will have to try to fix a problem without capital’s help—at best—or in the midst of a financial crisis—at worst. If no one panics, investors will make progress if there is money to be made, but may not work on the problem if it’s not profitable. To maximize efficiency in addressing important problems, our two groups must durably believe different things!

This is a challenge, and at the root of why so many people are mad at Bill Gates.

Talk amongst yourselves

Happily, the best state is the resting state.

Generally, the investor set makes more money when things are good, so generally you’ll hear capital allocators be more publicly sanguine than people with less money. Our cultural expectations help, as capital allocators know it would be bad (and low-status) if they panic loudly. So when they panic, they tend to do it quietly. Thiel, Zuck, Altman all have bunkers, but they know they’re not supposed to talk about it. Which is to say, Bill’s piece argued that we should not panic. Naturally, he addressed his peer group in the hope they continue to invest in a better future (in his definition, that includes a lot of investments in health, economic growth, and climate) and not in bunkers. On my graph, Bill is trying to get people in the top right corner to move to the top left. And this is usually societally optimal behavior.2

At the bottom of the chart, activists face the opposite challenge. There is no money, power, or influence if people don’t care. So, on any given topic, activists are, roughly, trying to fight apathy, to get people to panic sufficiently to drive collective action (move people from the bottom left to the bottom right). Which people? Activists are often people without lots of power as capital allocators3 and they naturally address their own class community; people with more voting power than capital. If activists can generate enough fear in the general public to drive demand for government action, then more progress can be made. This is also societally optimal.

So, the status quo gives us this (masterpiece):

Why everyone is mad at Bill Gates

In the US, it has been hard for the climate activist community to build their constituency and to keep everyone g’ed up sufficiently to drive government climate action, because, well, your average person in the US doesn’t care that much about climate change. American climate activists haven’t succeeded in generating the kind of social consensus on the issue that is apparent in Europe. The election of Trump, broad backlash against ESG, roll back of climate policy, and deprioritization of climate change culturally has meant that activists feel that the progress they’d made is under threat. So, they’re feeling a bit sensitive. The fragile coalition they’ve built to drive climate policy is coming apart.

So while Bill isn’t talking to them, the activists hear him. And in trying to tell his peers to not panic, Bill’s voice carries far enough that activists worry that it’ll reach the general public. If people outside of the capital allocator class listen to Bill Gates because he’s a famous and reasonable guy, and decide the climate crisis isn’t a crisis at all and things are probably fine, well then, activists will rightly worry that apathy will surge, and their leverage on collective action for addressing climate will fall, and we’ll all be worse off.

And, they’re not wrong? The Trump administration encapsulates many things, but one of them is the degree to which activists overestimated the amount that people care about climate. And, because activists rightly have assumed Bill Gates is “on their side” they’re mad, because when you combine Bill message (don’t panic) with his reach, you end up with something that feels to them like friendly fire.

And that is 1) why climate activists are mad at Bill Gates, 2) why we will consistently argue about whether or not we should be panicking, and 3) why this persistent disagreement (the rich insisting we shouldn’t panic, while laypeople somewhat panic) is actually the societally optimal level of panic in the face of a real threat.

Thank you to Nick, Susan, and Tamar for valuable feedback.

It’s worth saying, this is also Jigar Shah’s corner, and most of climate tech VC’s corner, and Lukas Walton’s corner, and the old DOE corner.

Except for financial speculation. This is what shortsellers are for—to prevent excessive optimism in the investor set and ward off bubbles that have high societal costs. Occasionally Michael Burry’s panic is very warranted.

Rich activists always have trouble here. If they keep the trappings and community of a wealthy person, they have to keep the “this is no time to panic” vibes up, which generates apathy in the broader community (see Obama and Hollywood climate activists for examples.) Or they adopt a “now is a perfect time for panic” energy that laypeople like, but suffer class consequences (see late night’s response to Trump, or Jane Fonda for examples.)

I love this piece